Positive Behaviour Support in school-aged children

My child has behaviours of concern, what do I do?

What is PBS?

PBS is grounded in the philosophical and scientific foundations of behaviour analysis but also draws on the values and methods of prevention science, implementation science, and, more recently, positive psychology. It is underpinned by the philosophy that human beings thrive in predictable spaces where expectations are clear, new skills are taught, and positive behaviours are richly reinforced. PBS is identified as an effective approach to supporting young children with behaviours that challenge them. PBS focuses on understanding the purpose of the behaviour and replacing it through adaptive alternatives by teaching new skills in a positive way (Grey, I., Mesbur, M., Lydon, H., Healy, O., & Thomas, J., 2018) and modifying the environment to be most supportive of the child’s needs, such as adjusted routines, access to tools, and skilled responders to the challenges.

What are behaviours of concern?

Behaviours of concern or BOCs, are defined by Schools Victoria as “escalated behaviours that can impact the wellbeing or physical safety of the child or people around them. This behaviour can disrupt day-to-day life and activities.”

Behaviours of concern are not:

- Stereotyped behaviours (e.g. hand flapping or lining up items)

- Age-appropriate responses to stimuli

Behaviours of concern might include:

- Sexualized behaviour,

- Violence causing harm to self or others,

- ‘Tantrums’ that extend for periods longer than 25 minutes multiple times a week

Where this is the case, there may be some further investigation needed.

Why does my child engage in behaviours of concern?

All children are still learning how to interpret their internal world and communicate it to those around them appropriately. Children with ASD, global developmental delays and other learning challenges can have difficulty communicating. Every child has their own set of strengths and difficulties and while some children are able to let their parents know what they want, it can be difficult for other children to notice and then communicate verbally things they do and don’t want, about how they feel or what they are afraid of. When children are unable to communicate easily or when attempts at communication are misunderstood, often the only option left for them is a behavioural response. Many of the challenging behaviours exhibited by children are better understood as communication attempts where verbal skills may be limited.

A behaviour or set of behaviours can be labelled as undesirable or challenging when they do not fit in with what the environment or society expects. In applying this social construct of the term ‘challenging behaviour’, the child is not the one with the challenge – it is the environment around that child that deems the behaviour ‘inappropriate’ or ‘challenging’. To the child, their behaviour is neither ‘negative’ or ‘positive’ or ‘challenging’, it is just their response to their environment or a specific situation. All too often the child is labelled as ‘challenging’ or ‘difficult’ when their behaviour is a response to the limitations of their environment in providing them with the support they need to communicate (Gore,et al., 2013).

What exactly does a PBS practitioner do?

Currently, in Australia, behaviour support practitioners are drawn from a range of professional backgrounds including psychology, speech pathology, occupational therapy, special education, social work, and learning disability nursing. Behaviour support practitioners typically are engaged with a child to conduct functional behavioural assessments and to write and monitor behaviour support plans. They offer specialist input, advice and support to the child, their family, and others in the child’s life including other practitioners such as early childhood educators, therapists, and support workers. Together, these people constitute the ‘team around the child’ to achieve the best outcomes for the child. Behaviour support practitioners will have a range of characteristics and skills which they bring to the relationship, and identifying strengths and gaps will ensure a ‘good fit’ between the practitioner, the child, and the team around them.

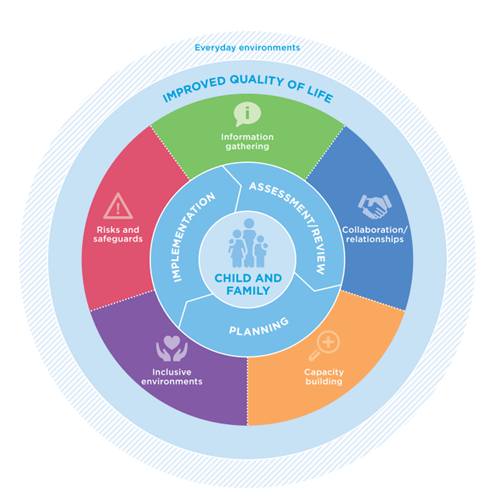

The primary aim of PBS is to achieve positive lifestyle experiences that commonly involve shaping and restructuring the environment to improve the child’s quality of life, and that of the people who support them, as defined by the child’s unique preferences and needs. Areas supporting quality of life can include respect and dignity, having choice and control, feeling competent, likeable and purposeful, having genuine friendships, participating in the school community, and having good mental and physical health (Aspect, 2017). PBS focuses on understanding the purpose of the behaviour and increasing positive behaviours rather than punishing negative ones.

Figure 1: The behaviour support process (Dew, et al., 2017).

What happens once PBS engages?

PBS is an approach which focuses on positive reinforcement for desirable behaviours. It is a “compilation of effective practices, interventions, and systems change strategies” (Sugai et al., 2004, p.10). The intention is to remove rewards “that inadvertently maintain problem behaviour” (Sugai et al., 2000, p. 16), by replacing them with clearly defined behavioural expectations.

PBS is based on an assessment of the social and physical environment in which the behaviour happens, includes the views of the child so that their needs can be met in better ways. PBS works collaboratively with allied health supports already involved and may make referrals to additional allied health where needed to achieve the behavioural and quality of life goals for the child and their family.

Typically, a behaviour support plan is created where families work with a group of people including school staff, parents/guardians or carers and a practitioner on a detailed plan to remove or minimise the triggers of the problem behaviour and, wherever possible, stop any accidental rewards for the behaviour. Consistency is key in behaviour change and having a behaviour support plan allows for all supports to be on the same page, having continuity of expectations of behaviour and response to challenges, helping the child to engage in more positive behaviours.

Once a plan has been developed, the behaviour support practitioner will work with the parents, school and other supports to upskill them in using the strategies in the plan, encouraging the child develop new skills and alternative, appropriate ways of communicating with others to express wants and needs.

References:

American Psychiatric Association. (2023). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed., text rev.). https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425787

Dew, A., Jones, A., Horvat, K., Cumming, T., Dillon Savage, I., & Dowse, L. (2017). Understanding Behaviour Support Practice: Young Children (0–8 years) with Developmental Delay and Disability. UNSW Sydney

Gore, N. J., McGill, P., Toogood, S., Allen, D., Hughes, J. C., Baker, P., … & Denne, L. D. (2013). Definition and scope for positive behavioural support. International Journal of Positive Behavioural Support, 3(2), 14-23.

Grey, I., Mesbur, M., Lydon, H., Healy, O., & Thomas, J. (2018). An evaluation of positive behavioural support for children with challenging behaviour in community settings. Journal of Intellectual Disabilities, 22(4), 394-411.

Kozlowski, A. M., Matson, J. L., & Rieske, R. D. (2012). Gender effects on challenging behaviors in children with autism spectrum disorders. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 6(2), 958-964.

Sugai, G., Horner, R. H., Dunlap, G., Hieneman, M., Lewis, T. J., Nelson, C. M., … Ruef, M. (2000). Applying Positive Behavior Support and Functional Behavioral Assessment in Schools. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 2(3), 131–143. https://doi.org/10.1177/109830070000200302

Sugai, G., Horner, R., Sailor, W., Dunlap, G., Eber, L., & Lewis, T. (2004). School-wide positive behavior support: Implementers’ blueprint and selfassessment. University of Oregon, Center on Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports, Eugene. Retrieved from Http://Pbis. Org/English/Handouts. Htm On, 8, 2004.

About the author

Meet Hannah, a positive behaviour support practitioner at KEO. With 6 years of experience working in the behaviour space, Hannah has refined her scope and landed in the paediatric area. Hannah’s main areas of interest are in neurodevelopmental disorders, trauma backgrounds and complex care teams.

Coming from a psychology background, Hannah uses the theory from psychology with the up-and-coming information on positive behaviour support to offer holistic and informed care. Hannah loves working in the community sector, understanding that being embedded in the lives of participants offers endless opportunities for success.