Physiotherapy for psychosocial disability

When thinking about therapy for clients with psychosocial disability, it is easy to imagine the involvement of occupational therapy in helping establish healthy routines, or the role of psychology in supporting emotional regulation. Though the role of physiotherapy may not be immediately apparent, physiotherapy plays a pivotal part in working alongside clients with PSD in collaboration with the above professionals to maximise function, wellbeing and quality of life.

The NDIS legislation reforms in October 2024 brought changes to the scope of physiotherapy involvement in supporting participants with psychosocial disability (PSD), with individuals’ physiotherapy funding being suspended due to these conditions not having an ‘inherent physical component’. Part of my role as clinical excellence lead for the physiotherapy team at KEO Care involves advocating for the role of physiotherapy in providing high-quality care to clients, including establishing the clear link between PSD and physical disability, referencing the current evidence base. In this blog I want to bring to light the essential role of physiotherapy, including why it is important that this support remains available for individuals with mental illness to achieve their functional goals.

PSD and physical function

Psychosocial disability is a term used to describe a disability that may arise from a mental health issue (NDIS, 2024). Within the NDIS, the term PSD is less concerned with the specific mental health diagnosis, but rather “the functional impact and barriers which may be faced by someone living with a mental health condition” (NSW Government, 2023). Such implications can restrict one’s ability to concentrate, access certain environments, interact with others, cope with time pressures and have enough stamina to manage daily tasks.

Mental health conditions that present with PSD include bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, complex post-traumatic stress disorder (c-PTSD) and chronic depression/anxiety. While these diagnoses have vastly different physiological mechanisms and resulting implications for the individual, some common attributes are consistent across these presentations. These features include an increased risk of chronic pain, reduced physical fitness and withdrawal from usual activities, contributing to a more sedentary lifestyle.

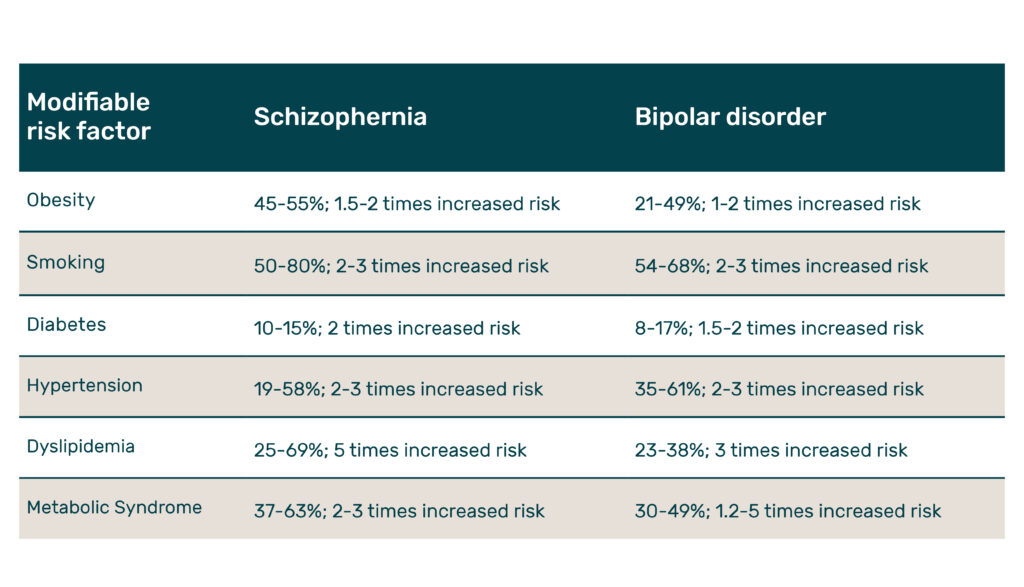

Individuals living with mental illness including schizophrenia and bipolar disorder experience far higher likelihood of chronic health problems – including obesity, high cholesterol, diabetes, and high blood pressure – compared to the general population. Combined with greater instances of smoking and lack of a sufficiently nutritious diet (in part due to side effects of antipsychotic medications, which will be discussed later in this blog), this can lead to a variety of health problems with physical consequences impacting functional participation.

(Mental Health Commission of NSW, 2016).

Side effects of anti-psychotics

Antipsychotic medications are widely prescribed for clients with PSD to manage the symptoms of mental ill-health, including hallucinations, delusions, confusion and disordered thinking – thereby helping support emotional regulation, relationships and participation in daily life. While these medications may lessen the severity of these symptoms, they can also have profound impacts upon other body systems.

Second-generation agents, including clozapine, olanzapine, and risperidone, can heighten the potential for cardiovascular complications due to a slowing down of metabolic processes and glucose abnormalities. On the other hand, first-generation agents (such as haloperidol) may have fewer metabolic impacts, though long-term use of these medications can result in tremors, rigidity, and uncoordinated movements – neuromotor effects that mimic parkinsonism. In both classes, sedation and weight gain are common, with weight gain experienced in approximately 80% of people using antipsychotics even after short term exposure (Alvarez-Jimenez et al., 2008). In either case, physiotherapy plays a pivotal role in minimising the functional impact of these medications upon the individual’s function.

Physiotherapist role

Given the vast and significant impact of PSD on physical health and wellbeing, physiotherapists form an essential role in the interdisciplinary team in supporting clients with PSD. Physiotherapists work closely with other allied health disciplines in ensuring holistic care and continuity of therapy delivery between all parties. This might include collaboration with occupational therapy (OT) in establishing routines around participation in physical activity to improve accountability with completion or working with psychologists in implementing a motivational interviewing (MI) framework for behaviour change related to participation in exercise.

Physiotherapists help promote healthy physical activity in a variety of ways to help meet the Australian guidelines for physical activity, which call for between 2.5 and 5 hours of moderate intensity physical activity each week for adults aged 18-64 (Department of Health, 2021). Current research advocates for the role of physiotherapy within the multidisciplinary team for individuals living with PSD, with best-practice guidelines incorporating aerobic and resistance components and individualised sessions using targeted motivational strategies.

What do the NDIS legislation changes mean for participants moving forward?

Reduction (or in some cases, restriction) of physiotherapy funding for individuals living with PSD has vast implications for the wellbeing and functional capacity for these participants, impacting their ability to reach their goals. Recent NDIS changes have meant that participants with functional disability as a result of mental illness who have previously been receiving physiotherapy support are no longer eligible. While allied health providers have been assured that an NDIA evidence committee will be established in the latter half of 2025, this interim brings a period of uncertainty for both physiotherapy practitioners and clients who require this crucial input.

As clinical lead for the physiotherapy team at KEO Care, I have a responsibility to physiotherapists in our organisation and to my own clients in advocating for the essential care we provide. Part of this includes incorporating high quality evidence in our KEO reports which play a pivotal role at NDIS review meetings for planners in determining participants’ funding for their next plan. Being proactive ensures that we remain industry-leading and helps safeguard ongoing physiotherapy support for our participants.

References

Alvarez-Jimenez, M., Gonzalez-Blanch, C., Crespo-Facorro, B., Hetrick, S., Rodriguez-Sanchez, J. M., Perez-Iglesias, R., & Vazquez-Barquero, J. L. (2008). Antipsychotic induced weight gain in chronic and first-episode psychotic disorders: a systematic reappraisal. CNS Drugs, 22(7):547-562. DOI: 10.2165/00023210-200822070-00002.

Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care (2021). Physical activity and exercise guidelines for all Australians. Accessed online: https://www.health.gov.au/topics/physical-activity-and-exercise/physical-activity-and-exercise-guidelines-for-all-australians.

Jibson, M. D. (2025). Second-generation and other antipsychotic medications: Pharmacology, administration, and side effects. Accessed online: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/second-generation-and-other-antipsychotic-medications-pharmacology-administration-and-side-effects.

Mental Health Commission of NSW (2016). Physical health and wellbeing: Evidence guide. Sydney, © 2016 State of New South Wales. ISBN: 978-0-9923065-8-8.

National Disability Insurance Agency (2024). Psychosocial disability. Accessed online: https://www.ndis.gov.au/understanding/how-ndis-works/psychosocial-disability.

NSW Government Department of Health (2023). What is psychosocial disability? Accessed online: https://www.health.nsw.gov.au/mentalhealth/psychosocial/foundations/Pages/psychosocial-whatis.aspx.

About the author

Tristan Brown is a Clinical Excellence Lead and Physiotherapist at KEO. With over 6 years of experience in clinical practice, Tristan is responsible for supporting a diverse community caseload which includes psychosocial participants, elderly clients and paediatrics.

Tristan appreciates being a member of a robust multidisciplinary team and loves delivering education and learning from his fellow team members. His approach to practice is creative and collaborative, so he and his KEO colleagues can work effectively together towards the best outcomes.